VILLA SOLEADA

A community partnership that started over a decade ago

The Past

The statistics in El Progreso’s largest riverbed shanty slum—known as Siete de Abril—were grim. Every single family battled with generational poverty. Running water, adequate housing, electricity, land titles, and sewage system were nonexistent. Gang violence, alcoholism, drug abuse, chronic unemployment, undocumented emigration, and malnutrition were rampant. Local authorities described the place as “the hardest slum in the city.”

A household survey revealed that 0% of the residents had graduated from high school. Not one person had graduated.

The Project

In 2005, we began meeting with community members on a daily basis. Together, we attempted to tackle a simple question: could an entire community in Honduras lift itself out of generational poverty if not just one but all its challenges were addressed comprehensively?

In 2007, the village council decided to relocate their community. Our organization bought a large plot of land in northern El Progreso. Funds were raised in the US for construction supplies. Following the lead of community members, we organized, created a plan, and began building together. Over two years, 13 acres of wilderness turned into a village.

In 2009, 44 families moved into the newly built village. For the first time, they had

access to a water well, electricity, land titles, adequate housing, and sewage system.

Yet many challenges still remained: generational poverty, illiteracy, chronic

unemployment, drug abuse, violent crime, and malnutrition.

The School

In 2012, the families asked our organization to build the one thing missing in their community: a school.

A dream emerged. It was so profound yet so simple: one day, every child from the community would be a high school and college graduate.

Inspired by their vision, our team has been striving to achieve a 100% graduation rate in the community. We believe that our students can become self-sufficient, productive adults who can make a positive impact in Honduras. Together, we can help Villa Soleada become a sustainable, model community.

Antonio’s Story

“I want to keep improving. Improve my house. Fence it. To make it better for my daughters. I want them to have the best.”

– Antonio Reyes, resident of Villa Soleada and assistant foreman for OTS since 2007

I use to live in Agua Blanca North. It is close to Brisas de la Libertad. I lived with my in-laws and my wife there since I was 18. My in-laws supported me a lot. My mother-in-law was like a second mother. My wife worked at the factory in El Porvenir. My family moved at the same time and settled at La Siete. Everyone took a piece of the land and made their house. I helped make a wooden house for my mother with my brothers, but they did not have papers for the land…We found that this land (now, Villa Soleada) was for sale, and we all went to see it– Wincho, Chilo, my dad, my uncle Daniel, my mom’s brother. Nearly, the whole family and other people from Siete went to see it also. Shin said, “If everyone likes it here, we are able to purchase it.” So he did. I remember very well that he bought 100 shovels and 100 pickaxes. And he said that 400 Americans will come for the first time to help make the houses in Villa. Then, we began constructing the houses for two years.

Employment & Job Training

Unemployment and income inequality are major challenges in Honduras. For a family of four surviving on one minimum wage—$364 per month—each family member must live on approximately $3 per day.

Many residents in Villa Soleada were unemployed or lived on $1 to $3 per day prior to moving into the community. We began employing some of the residents as soon as the community was built. Now, the organization provides jobs—in administration, construction, youth work, driving, cooking, etc.—to around one fourth of the families in the community. Several families have two to three family members working for the organization and have a standard of living considerably higher than before.

Through microcredits, finance workshops, and job training, many others have started small businesses or work in the private sector. There are a number of ways that our network can support the local entrepreneurs: getting haircuts in Villa Soleada, buying snacks at the corner shops, buying ice cream from mobile vendors, getting clothes tailored, getting shoes stitched, buying local souvenirs, etc.

Eduar’s Story

Eduar lived with his family in a house made of nylon, cloth, and mud in the old riverbed community. He walked an hour each day through gang territory to the closest school. The odds were against him—62% of students in Honduras in his income bracket dropped out of school by age 16. When he wasn’t studying, Eduar spent his time helping his father recover from an illness or played soccer. Eventually, his father recovered and participated in the construction of Villa Soleada as a brick layer. In 2007, Eduar and his family moved into his new house in Villa Soleada. It was there that he learned to use a computer and the internet. Those skills would come in handy shortly after.

In 2017, he became the first boy to graduate from high school in the community. Immediately after, Eduar began working for the organization part-time job as a general assistant. There was always something special about Eduar. He was hard working, honest, loyal, and quick witted. He impressed the team and was quickly promoted as the Director of Logistics for OTS. Both his parents work for the organization—his mother as a chef, and his father as a construction worker. Eduar is now married and building a cinder block home with his income.

High School & University Scholarships

When the Villa Soleada Bilingual School opened its doors in 2012, many teenagers in the community were too old to enroll—the highest grade we offered at the time was only the second grade. We started a scholarship program to help the teenagers who were unable to attend the bilingual school. The teenagers had a choice to attend the local public school, a weekend GED program (for those who worked during the week), or a vocational academy. The cost to send a teenager to a public school or weekend GED program is around $300 per year. The cost for a student to attend the vocational academy is about $1,000 per year.

As many of our scholarship students have become first generation high school graduates, our next goal is to help them attain college diplomas. The cost for a student to attend college is about $1,000 per year.

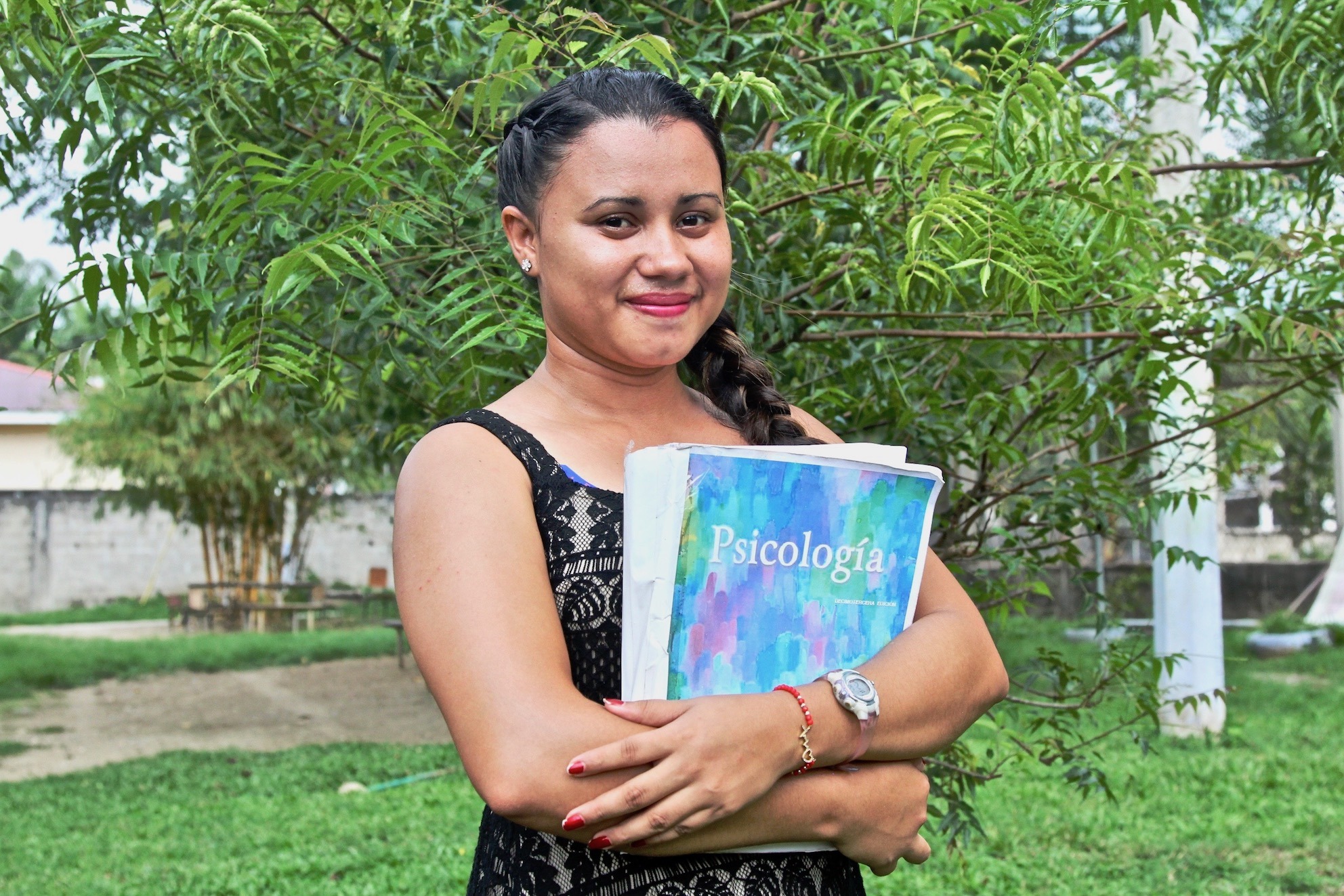

Osiris’s Story

One generation ago, there were no high school graduates from the community—there was a 0% graduation rate. The youth is changing the future of Villa Soleada. One of the them is Osiris. As one of the first high school graduates from Villa Soleada, Osiris is the very first youth from the community to enroll in a university. She is now a first-generation college student studying psychology at Universidad Cristiana de Honduras (UCRISH).

While studying, Osiris works full-time as a teaching assistant at the Villa Soleada Bilingual School. After working with Kindergarteners all day, she spends the rest of her day studying and completing her coursework late into the night. Balancing full-time work and school is no easy task.

If you’ve volunteered with us before, many of you may know Osiris’s father, Antonio, a true leader who has been on our construction team for over a decade. He’s shown true humility, dedication, and perseverance since the very beginning. Olimpia, Osiris’s mother, also works for the organization. She is a lead chef at the Villa Soleada kitchen. “My family has always been my inspiration because even though my parents have not studied they inspire me and guide me on the right track,” says Osiris.

Homes

The homes in Villa Soleada are constructed with cinder blocks and reinforcement steel. Every house withstood the 7.3 magnitude earthquake in 2009. Each house has three bedrooms, a bathroom, shower, and wash basin that connects to the main sewer system. The community gained access to electricity when we installed an electric grid in 2009.

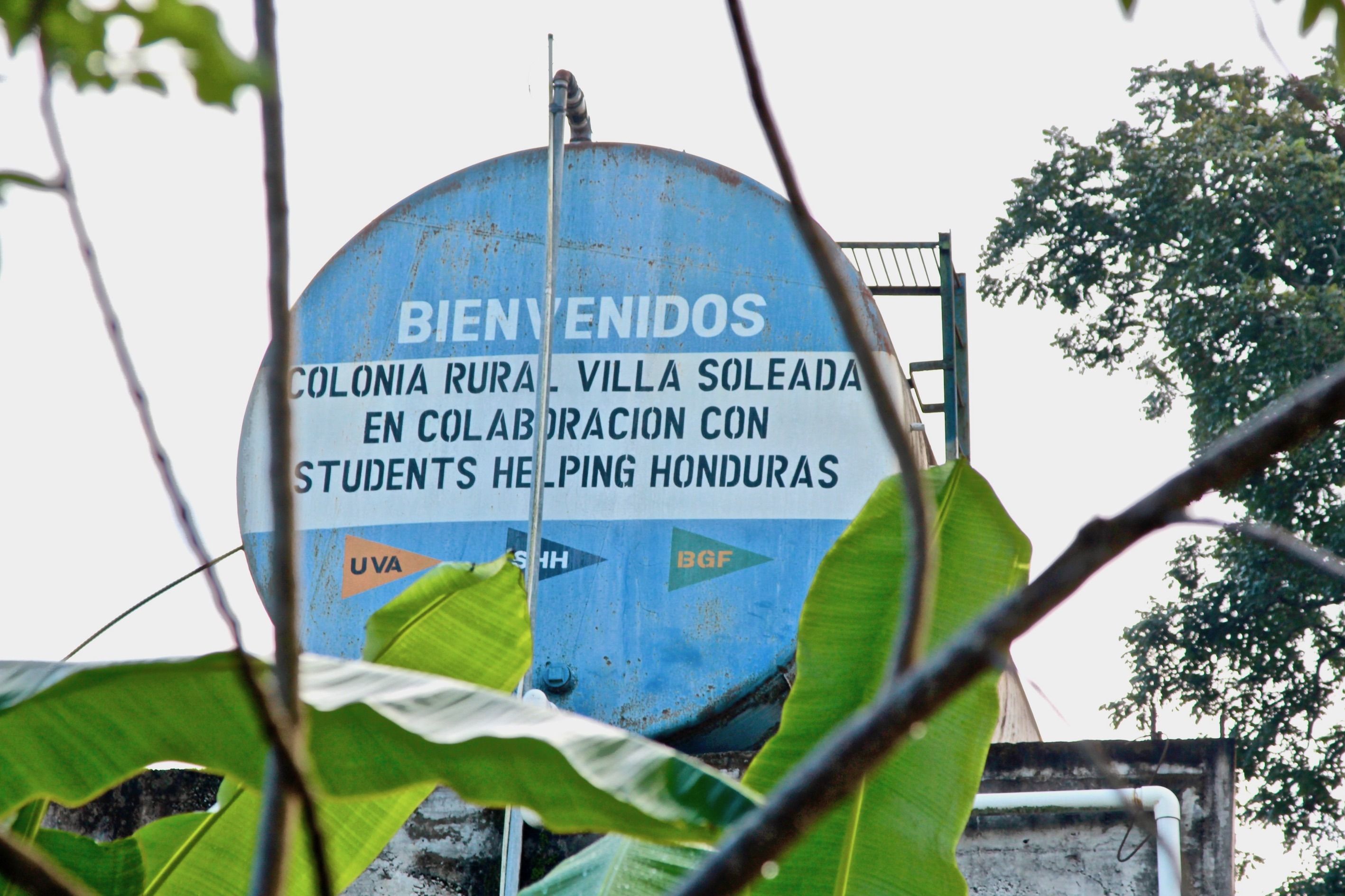

Water

Access to potable water is a luxury in many developing countries like Honduras. In 2008, we dug a well in Villa Soleada and connected it to a water grid and storage tower. In 2017, we added a gravity fed water system by tapping into a natural spring many miles up in the mountains.

Sewage & Sanitation

Many communities in Honduras lack access to a proper sewage system. As a result, families build pit latrines in their backyards which can contaminate the area and cause preventable diseases such as worm infections, cholera, dysentery, and diarrhea. The Villa Soleada water supply chain ends at the waste stabilization ponds located in the lowest corner of the community. Through gravity, wastewater flows out of each building and into an underground pipe system that was built by hand. The wastewater flows into the two waste stabilization ponds that begins to break down the pathogens. It is a low tech system that requires only sunlight and minimal maintenance.

Soccer

For the people of Honduras, much of their free time can revolve around soccer: playing it, watching it, or discussing it. For many young people, becoming a professional soccer player is a way out of poverty. For every community, soccer is a uniting force that keeps vulnerable youth busy and out of trouble.